Anne Thibault was born in 1966 in Hull (Quebec). After her collegial studies in both arts and pure and applied sciences, she finally opted for the arts and graduated from the Université du Québec en Outaouais with a Bachelor’s in plastic arts and from Ottawa University with a Master’s in plastic arts. She then specialized in graphic design at the Université du Québec à

Her meeting with Université de Montréal biology researchers in 1995 was a turning point in her career. Anne Thibault drew inspiration from the scientific universe; her quest to find ”living pigments” first led to the study of plankton and microscopic algae. Phytopathologist Peter Newman then showed her artistic potential behind mold. She learned that it was easy and harmless to assemble cultures that would present an infinite variety of colors and textures. Since then, she built installations which met half way between arts and sciences in collaboration with microbiological research and schooling in Canada and abroad.

In 1995, Anne Thibault worked on a mobile and living laboratory project entitled La chambre des cultures. The exhibit was displayed until 2001 in many artist center in Canada and abroad. Thibault had her work displayed notably in Canada, Finland, Spain and England. Examples of which include her recent participation in the Intrus/Intruders exhibit at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (2008-2009) and Dé-con-structions at the National Gallery of Camada (2007). Her art is on display in collections belonging to the Musée national des beaux-arts de Québec, the City of Ottawa, and the Ottawa Art Gallery. Anne Thibault also created more than ten pieces integrated to architecture and the environment including the Cégep de Granby (2011), the National Circus School of Montreal (2010) residences, the Hôpital psychiatrique de Malarctic in Abitibi (2009), the Hôpital de Gatineau radio-oncology service (2009) and the Sainte-Julie municipal library.

Artwork description

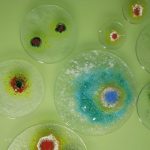

Compact glass pellets – like droplets of water – reference the ancient theory of panspermia that points to spores and dust from stars that landed in the morning dew as the source of the life on Earth. A French legend put forth the theory that mushrooms originated from the Moon. They were designated as ”pure remnants of stars”, ”lunar phlegm” or ”devil’s phlegm”. The artist invites us on a microscopic journey, uniting fables, magic and biology into one work of art.

Each pellets is unique, made of enamel and colored oxide powder cast in glass. Inspired by real bacteria cultures, the pellets show the infinitely small world. Their lightly convexed surface, moreover, reminded us of the Petri dishes, in which scientist ”breed” micro-organisms.

The green-painted wall slightly tints the glass boards on which the glass pellets seem to float and agglutinate, as living organisms do in Petri dishes. Also, when viewed from far away, the shapes’ positions on the glass background suggest the forming of a constellation.

Although not strictly illustrated, the piece also evokes the research vocation of the pavilion’s main occupant, the Institut for Research in Immunology and Cancer (IRIC).

Annie Thibault accords great importance to how her works of art created for the Programme d’intégration des arts à l’architecture et à l’environnement follow her artistic process. She loves this challenge which allows her to explore new avenues of creation, despite the pieces’ lasting and secure qualities constraints, contrary to the spontaneity and ephemerality she practices in studio.

For the first time with this work, Annie Thibault uses the glass pellets to imitate the spores. She began by using water colors to paint the results she observed in the dishes. Master glassmakers, thereafter, must see to merge the pigments properly into to the glass, not without having made hours of research in order to control the oxides’ reaction when heating the glass. The artist believes that the surprises that can arise from the melted pigments are a way to transpose the organicity into the sustainability.

Thereby, this piece is consistent with her artistic method, which is based on intuition, manipulation … and error. When manipulating the living, errors are important, and one must know, in sciences and in arts, how to turn them to our advantage. This can lead to important discoveries: for example, penicillin was discovered by accident. Annie Thibault found new sources of inspiration with the errors she describes as ”deviant spaces”.

Her process is similar to bio-art, a new movement of contemporary art where artists use living things as a means of expression.